Contract Operations OKRs: How to Align Objectives and Results

For years, key performance indicators (KPIs) have been the standard for measuring contract...

Catch up on all the latest news, blogs, Ken Adams advice, and more.

For years, key performance indicators (KPIs) have been the standard for measuring contract...

Contracts define relationships, obligations, and expectations across every area of business. As...

Managing contracts in healthcare requires precision, compliance, and efficiency. Every agreement,...

Contracts run the business.

Vendor Management Checklist: 10 Steps to Smarter Vendor Selection

Every contract carries risk—financial, legal, operational, and compliance. Without a structured...

AI contract review tools are revolutionizing how legal and business teams identify risk, accelerate...

Originally published with WorldCC

Contract renewals can be deceptively tricky. While they may appear routine, every renewal is an...

Every fall, a familiar scene plays out in organizations everywhere. Department leaders gather their...

By Lars Mahler, LegalSifter “Agentic AI” is everywhere—analyst maps, vendor decks, buzzy demos. For...

Is your contract review process built for speed, or stuck in first gear? Are you being asked to “do...

Law firms are under increasing pressure to review contracts faster, operate within tighter budgets,...

Webinars

Join our live demo to see how ReviewPro works seamlessly inside Microsoft Word, using your playbook or ours to apply consistent, attorney-quality redlines automatically.

Webinars

Learn how to leverage contract data for better business decisions with Datadog and LegalSifter. Join the webinar to unlock the value of your contracts.

Webinars

Discover the synergy of AI and Human Expertise in transforming contract operations with our webinar recording from AI Tech Week.

Webinars

Gain insights from legal industry experts on navigating the CLM market with AI. Discover strategies to optimize contract operations and enhance business decisions in this dynamic webinar.

Blog

Learn how to protect yourself in cloud computing agreements. Discover the top 5 mistakes buyers make and the questions you should be asking about your data. Join the webinar with David Tollen, a leading authority on IT contracts.

Blog

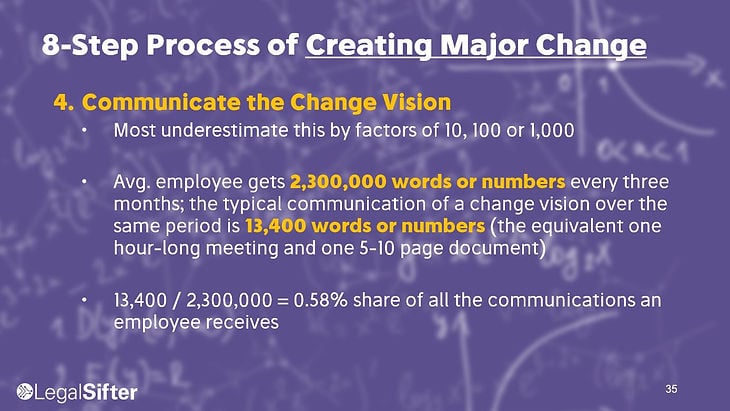

Discover how to effectively drive change in the legal profession with John Kotter's 8-step process. Watch our free webinar to learn best practices for change management in this rapidly evolving industry.