The Accidental Contract Manager: A Guide to Scaling a Nonprofit

By Matt Darling, LegalSifter You didn't get into the nonprofit world because you have a burning...

Catch up on all the latest news, blogs, Ken Adams advice, and more.

By Matt Darling, LegalSifter You didn't get into the nonprofit world because you have a burning...

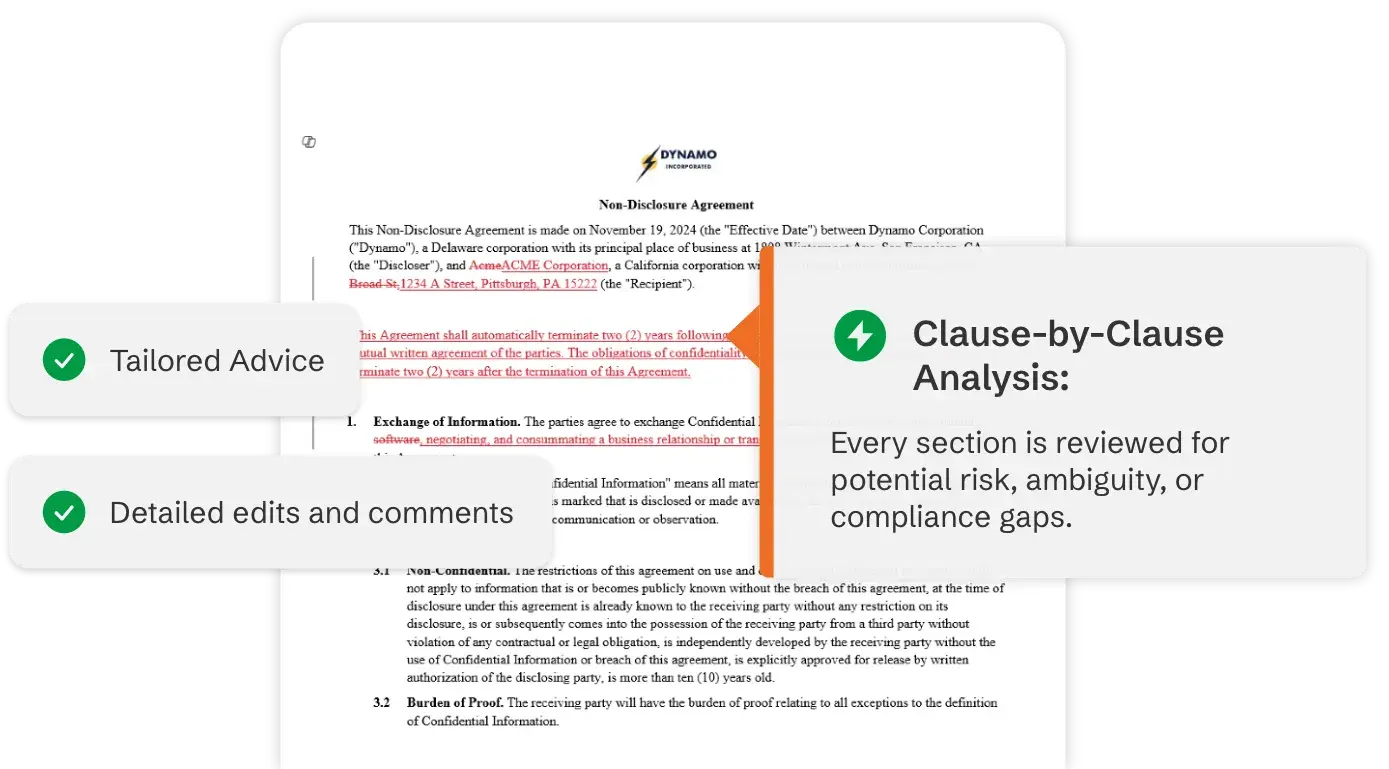

A New Model, Built for Real-World Legal Workflows The rise of generative AI has made it easier than...

By Buddy Broussard, LegalSifter As AI contract review software becomes more accessible to legal and...

By Matt Darling, LegalSifter Everyone obsesses over cycle time. How fast did legal turn that NDA?...

By Matt Darling, LegalSifter You find the perfect candidate. The client loves them. The deal is...

By Matt Darling, LegalSifter You know what kills deals? Time. Not price objections. Not competitor...

By Buddy Broussard, LegalSifter Most experienced business leaders are comfortable reviewing and...

Indemnification is one of those contract terms that can look like “boilerplate” until something...

Whether you’re drafting a contract for the first time or refining your existing process, having a...

Does your organization have a clearly defined contract approval workflow? Or do approvals drift...

For years, key performance indicators (KPIs) have been the standard for measuring contract...

Contracts define relationships, obligations, and expectations across every area of business. As...

Managing contracts in healthcare requires precision, compliance, and efficiency. Every agreement,...

Webinars

Join our live demo to see how ReviewPro works seamlessly inside Microsoft Word, using your playbook or ours to apply consistent, attorney-quality redlines automatically.

Webinars

Learn how to leverage contract data for better business decisions with Datadog and LegalSifter. Join the webinar to unlock the value of your contracts.

Webinars

Discover the synergy of AI and Human Expertise in transforming contract operations with our webinar recording from AI Tech Week.

Webinars

Gain insights from legal industry experts on navigating the CLM market with AI. Discover strategies to optimize contract operations and enhance business decisions in this dynamic webinar.

Blog

Learn how to protect yourself in cloud computing agreements. Discover the top 5 mistakes buyers make and the questions you should be asking about your data. Join the webinar with David Tollen, a leading authority on IT contracts.

Blog

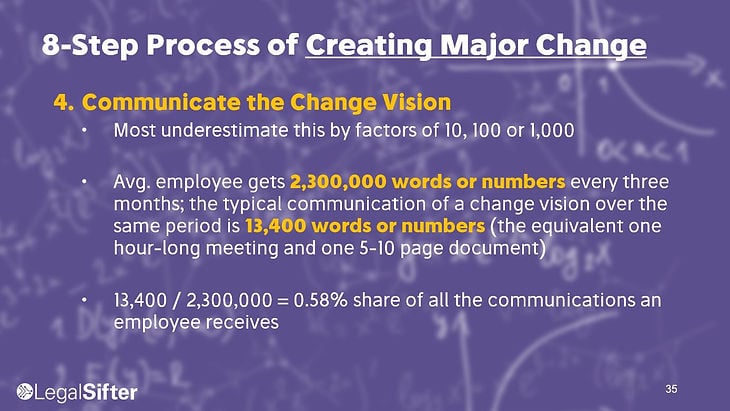

Discover how to effectively drive change in the legal profession with John Kotter's 8-step process. Watch our free webinar to learn best practices for change management in this rapidly evolving industry.